Between the Present and Eternal

Leaving a liturgical tradition and finding a worship home in a non-denominational church has given me an appreciation for the meaning of worship, community, and the supernatural world we aspire to.

Several years ago I had a conversation with a young man aspiring to be a pastor. I asked him which denomination he wanted to serve, to which he quickly answered, “I’m not any denomination. I’m just Christian.”

“Ah,” I said. “So what will you say when someone in your flock asks you to baptize their baby?” He answered by explaining that he would only do full immersion baptisms. “So, then you are a certain kind of Christian that doesn’t believe in infant baptism,” I said. “Do you consider Lutherans and Presbyterians Christians?”

“Yes,” he replied, with a weakening conviction in his voice. That conversation opened up his mind about the importance of ecclesial identity. Baptizing infants is based on certain assumptions regarding how one enters into covenant with the church. It presumes that parents have the God-given authority to bring their children into covenant and is a separate act from an actual profession of faith in Jesus that they hope their children will one day make. In this model, the church acts as a mediator of sacramental grace and blessing. It’s not magic, and it’s not a guarantee that the child will grow up faithful, but it is a statement of faith by parents that they intend to raise their children with the teachings of the church for which they belong. For others, baptism is an act of obedience to a Biblical mandate. It can only be pursued by a person old enough to make a public proclamation of their relationship with the Lord Jesus Christ. These distinctions regarding the practice of baptism point to a larger reality of what people believe about the interaction between the present world and the supernatural world; the Church Militant (on earth) and the Church Triumphant (in heaven). The struggle for ecclesial identity, another way of answering the question every Christian should ask himself, “To which denomination do I want to belong?” is bound up with what one believes and how one interacts with the presence of eternity in our present mortal lives.

My search for ecclesial belonging started in high school and came to a decisive turn in my 20s when I converted to the Roman Catholic Church.1 I served in Catholic parish ministry with an MA in Pastoral Ministry for twenty-five years until my settled Catholic identity was interrupted by a clear calling from God to revisit my assumptions and beliefs in 2017. It’s been six years of worshiping and living life as an Evangelical Christian, and I find myself resigned to the idea that as a believer in the Lord Jesus Christ as Savior and Redeemer, I will always feel homeless in this world. I have clung to the following C.S. Lewis quote and never more than in this present moment:

If I find in myself desires which nothing in this world can satisfy, the only logical explanation is that I was made for another world (Mere Christianity).

There is a broader spectrum of practice in Protestant worship and sacramental life than I had ever imagined during my twenty-five years as a Catholic apologist. My formation as a Catholic was decidedly post-Vatican II and steeped in pre-internet, low-level and over-simplified apologetics. I had reduced all Protestants to the most basic common denominator caricature as “it’s just me, Jesus, and whatever I want to believe from the Bible” believers and the Catholic Church as the romantic figure of world history that had withstood the slings and arrows of all errors. Both are oversimplifications and caricatures. The variation in worship and beliefs extend further than just the polemical extremes that I had reduced them to: liturgical vs non-liturgical and sacraments as either efficacious means of grace vs merely symbolic and memorial in manner. The nuances and shades between those extremes have surprised me. These variations are legitimate in their claims (for the most part) just as the variations in the first century church existed between Jewish, Gentile, Greek and Hebrew communities under the unique conditions of Roman rule and clashing empires. Other than some clues in the Bible and very early documents such as the Didache, Christian worship and practice was not assigned very many specifics by the New Testament authors nor, contrary to Catholic claims, from the Patristic Fathers. From where I sit now, as a fairly well read but by no means scholarly believer, most denominational differences in worship and faith practice have valid Biblical or historical explanations behind them.

In a You Tube interview with Javier Perdomo I was asked, “Why Evangelical? Why not a more liturgical church?” Even though I knew the question was coming, I found that my prepared answer was insufficient. I came to the realization in that moment that I was Evangelical because that’s where God led me. What better way to “reset” my beliefs and assumptions about this present life with Jesus in such a matter that my worship and faith life might reflect my beliefs about the eternal. That is to say, leading me to an Evangelical, non-denominational community in the very specific way He did2 was maybe God’s way of stripping away all the historical ornaments of liturgical traditions that were obscuring the basic truths of the Christian faith. My faith and worship needed to be simplified and less obscured by the historical and cultural add-ons. Faith must be the starting the place. A priest I knew well in my Catholic days was fond of saying, “Keep the main thing the main thing.” I doubt I will stay this way forever, but for now I am thriving in my spiriual growth in a non-denominational, non-liturgical community.

Liturgical aesthetics are beautiful, but often distracting. I do not renounce the beauty of high church worship, but it is clear that as sensual human beings, we can experience a kind of “capture” by the aesthetics at the expense of genuine and relational faith to the person of Jesus Christ. On the most basic level, a relationship with Jesus is established without need of liturgy, days of obligation, or even sacraments. The practices of worship and fellowship deepen and enhance a thriving relationship with the Lord. They might even inspire a person who doesn’t believe to investigate further, but they are not sufficient in and of themselves. No matter how many smells and bells and choirs of angels present in worship, the Holy Spirit and the believer’s own surrender to his need for a Savior is the a priori condition.

The beauty and the art in high church worship and practice enrich and inspire. In fact, many Evangelicals, after they overcome their cringe response toward anything that offends their Puritan based instincts, discover that they are starved for classical beauty in their worship. As a Catholic, I had allowed my love for my community and my identity in ministry to replace my relationship with Jesus so much so that even the liturgy began to feel empty. The best analogy I can think of is if everything you ever eat is covered in chocolate frosting with sprinkles, eventually, you no longer taste the frosting and sprinkles. You look for the food underneath it. For me, when I moved across the country from Washington state to Tennessee and had to begin building relationships with a new community of faith, I found some very nice people, but my faith was bland…it was connected with my identity as a Catholic and not a vibrant faith with Jesus. There’s plenty of time to add the beauty back if that’s where the Lord leads me, but the critical task of “going basic” in faith and a daily surrender to the cross and His Word seemed to be what I needed and God led me to that exact place at Grace Fellowship Church.

Besides a hollow faith, the years of fighting what I saw as a crumbling of moral credibility began to take its toll. I could no longer call myself Catholic when it became clear that the institutional trappings of the Roman Catholic Church served to protect truly evil people (hence, rendering the Church’s claim of divine protection from the gates of hell as irrelevant and patently false). I could no longer see the church that Jesus refers to in Matthew 16:18 as an earthly institution. An institution governed by men could no sooner be guaranteed divine protection by its own existence than the Holy Spirit could be kept in an ornamental cage. Are there non-Catholic churches overcome by the gates of hell? I imagine so, but they do not make such grandiose claims as to be the “one and only” protected. In the same way a man can be evil, an earthly institution can be as well. The holiness in the Roman Catholic Church exists solely in local congreations. The institution bears no resemblance to the body of believers described in Paul’s letters. I think the more modest and reasonable proposal is that the church protected from error is invisible to the human eye and covers the globe. That church is a mystical union of communities who advance the Great Commission by preaching the gospel and baptizing in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

That being said, I have come to appreciate how worship and fellowship reflect not just a relationship with Jesus, but also our beliefs about eternity, most especially the First and Last Things. As an Evangelical I miss the solemnity in worship or any sense of historical inheritance that stretches farther back than Billy Graham (worst case) or the Reformation (best case). While the sensory appeal of liturgical worship with its timeless connection to the early church recalls the invisible, timelessness of heaven, the more contemporary praise and worship of Evangelical worship and the lack of ritual shakes me out of myself and invites me to worship in the here and now with the Living God on His throne. The ancient practices are beautiful, but they don’t always convey what is real and immediate.

Another example of experiencing eternity in a real and immediate way happened when I attended a conservative Presbyterian prayer service. It reminded me of the need for community confession and the value of treating confession as a Biblical (dare I say, sacramental?) command. This particular Presbyterian community’s practice of a corporate monthly prayer service included a very thorough examination of conscience and confession, but did so in a way that was liberated from canonical chains or prayer formulas (as practiced in the Catholic Church).

A Catholic reader might think I am just trying to escape accountability from the “one, true church.” Others may think I am just fickle and hard to please. Back to the Lewis quote, “If I find in myself desires which nothing in this world can satisfy, the only logical explanation is that I was made for another world.” For me, this speaks directly to my ecclesial identity and my desire to worship in a way that is both genuine and also reflects my beliefs about eternity. These six years of praying, reading Scripture, worshiping in a faithful community, and learning from a variety of theologians (far more scholarly than I) who examine these same questions regarding worship, denominational differences, and historical theology have impressed upon me how deep and far reaching the faith and practice of Christian worship is. The fact remains, that I will always feel homeless on this side of heaven when it comes to worship and community because until I am home with the Lord, there is no worship that will grant me the full vision of heaven (though I am aware that the mass and the liturgical worship of mainline churches are fashioned to participate in the worship of heaven as depicted in the Book of Revelation 3). Yet, what anybody has to offer toward that Biblical and apocalyptic vision will never satisfy the longing to be united with Christ. Saint Augustine wrote, “You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our hearts are restless until they rest in You.” A lover of Jesus walking in the Holy Spirit will always long for more. Recall David’s words in Psalm 42:

“As the deer longs for streams of water, so my soul longs for you, O God. My soul thirsts for God, the living God. When can I enter and see the face of God? (NASB, vs 1-3)

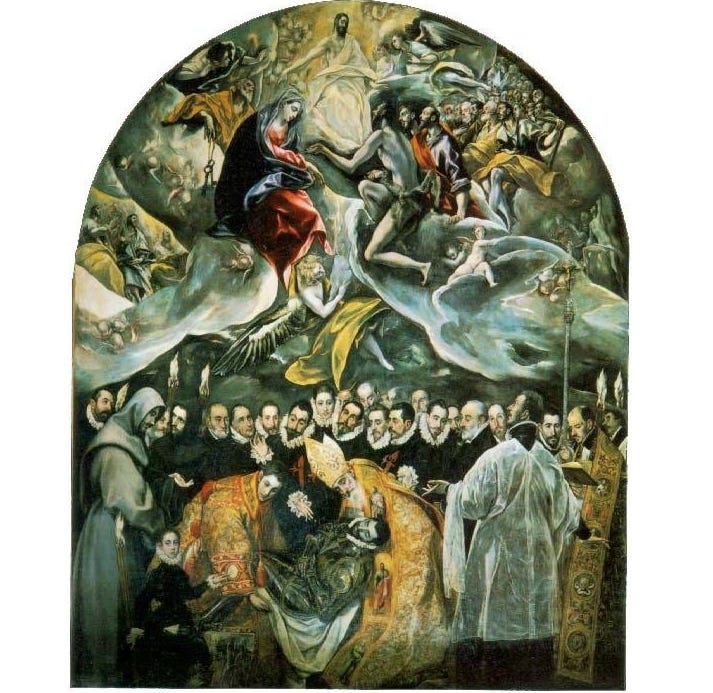

A final image and thought to leave with the reader regarding the power of worship and how it relates to our sense of eternity in our midst. It relates to the painting at the top of this post which depicts a funeral liturgy. An interesting note about the word, “liturgy,” is that it literally means, “work of the people.” While worship is necessary for our benefit (not God’s), liturgy, like art, is a beautiful attempt to participate in the heavenly worship. In the book, How to Inhabit Time, Calvin University professor, James K.A. Smith reflects on the theme of El Greco’s famous painting, The Burial of Count Orgaz. The painting depicts the funeral for Count Orgaz, a 14th Century public official from the town of Toledo, Spain. At his funeral are several other Biblical and historical figures depicted with their particular symbols or “badges of their vocation” (i.e. Stephen the Martyr with a stone, John the Baptist’s sackcloth, Peter and the Keys to the Kingdom, etc.). As Augustine, 4th century African bishop, is seen holding the dead Count Orgaz in his arms, surrounded by his contemporaries of the day, above them are clouds and a “birth canal” leading to heaven. Those in heaven, including “Mary and John the Baptist, interceding before the ascended Christ, Peter and Paul attending” are seen ushering in the Count’s soul (Smith, How to Inhabit Time, “The Sacred Folds of Kairos,” pg. 76). Dr. Smith summarizes the theme of the painting:

What El Greco achieves here is not some bland “eternalization” that denudes humans of their history…..[nor] a diminishment of history but some kind of curvature in time, bending toward the One who was born to history “in the fullness of time” and who is, at the same time, before all things and the end of all things. …...In the temporal riot of El Greco’s masterpiece, the future touches the present just as resurrection reaches into the tomb. The heaven “above” is also a future to come, a future that is now. As one critic observes, at the center of the painting we see an angel bearing Orgaz’s childlike soul “through a sort of birth canal of clouds to heaven,” in death reborn.The light of that future illumines [sic] all the faces looking toward it in the present below. Time here is bent and folded.

This lofty reminder of the glory to come after this life makes me wonder if there is any worship on this side of heaven which accomplishes what the faithful long to express: a worship that is pleasing to God and one that elicits a unifying and transcendent felt presence of God. Paul gives plenty of instruction to the Corinthians on the proper behavior and attitude appropriate to worship. His admonishments are towards prideful behavior that causes division, jealousy, or scandal in the community, yet he provides no instruction for what a truly worthy worship looks like. I have felt God’s presence and promptings during the most casual, evangelical contemporary worship just as often as I have during a high mass. Is the fact that I “felt” something evidence that the worship was worthy? Was it my state of heart and mind that predisposed me to feeling God’s divine presence, or was it some style, liturgical element, or sincerity of the presiders and attendants?

For now, I worship and “fellowship” with a beautiful community of believers who love the Word of God, preach the Good News of salvation through Jesus Christ, humbly serve one another and the non-believing community with material and prayer support, evangelize through mission support and continually seek to grow in the gifts of the Spirit, admonish one another lovingly, repent, and baptize in the name of a Triune God. They respect historical Christianity, but are mostly preoccupied with acts of love and mercy for one another. This side of heaven, I believe these qualities are the best any Christian community can offer. I am eternally grateful and have never felt the love of Jesus more. My worship and faith practice are directed in a most imperfect and incomplete way toward my heavenly home with my heavenly family. Amen.

I tell the story of my conversion in my post, “My Roman Holiday” on the Impolite Company Substack Newsletter.

While struggling with my Catholic identity, I ernestly prayed daily for God to bring someone on my path who could counsel me through this crisis. I had endured years of the tepid Catholic response, defending the truly evil behavior of the insttutional church with platitudes such as, “We are all sinners….. .” My answer, “But these sins are being protected by the so-called “one true church” which claims to be protected from being overcome by “the gates of hell.” On the other hand, I knew that if I went to a Protestant pastor, I would likely be dealing with someone whose bias against the RCC would be based on caricatures and misrepresentations. I needed a unique person who could help me navigate through my truth questions without bias against one or the other tradition. After months of praying, while waiting for my car being serviced, I was alone in the waiting room with a man. A conversation ensued and two hours later we were in the parking lot in front of both our finished cars exchanging emails. He had a very grounded understanding of church history, knew the works of patristics as well as the popular Catholic apologists but was an evangelical Christian himself. He was raised Catholic and was in the process of encouraging his own father to return to the RCC. Over the next few years I came to know his beautiful family as he served as a primary mentor. He was bold enough to challenge me when my criticisms of the RCC were from a place of pride. He often took the side of the RCC in our conversations. I started attending his church, which is the community where I worship today, Grace Fellowship Church in Kingsport, TN.

For a description of liturgical practices and how they correspond with sections in the Book of Revelation, go to the Archdiocese of Washington blogpost, “The Biblical and Heavenly Roots of the Sacred Liturgy”